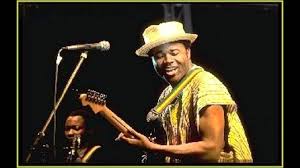

Biggie Tembo

By Kamangeni Phiri

IN most action movies, heroes don’t die, they rarely do.

They are invincible; evade every danger that comes their way and where their skills appear to fail them, they simply bluff their way out of trouble aided by either a charming smile or good looks.

Comparisons can be drawn between the mythical hero and the late musical icon, Biggie Tembo, a Zimbabwean singer, songwriter and guitarist.

Tembo led Zimbabwe’s first successful musical export, The Bhundu Boys, into conquering Europe and the world from the mid to the late 80s. He was the brains, the voice and the face of what was arguably Zimbabwe’s finest boy band. The Bhundu Boys arrived at Heathrow Airport, London, in 1986 as a known talented group from Zimbabwe although little was known then about their live performances.

“Nevertheless, Tembo’s rallying cry of ‘Mhururu! Mhuru! Mhururu!’, the cantering snare drums and the guitar lines were soon getting audiences on their feet, jit-jiving and grinning from ear to ear in, at first, pub backrooms, and gradually larger dance-halls around Britain,” wrote Philip Sweeney in Biggie Tembo’s orbituary published by the UK’s Independent paper in 1995.

But the last days of his life dispel the myth that heroes are invincible.

The late jit heartthrob’s death in July 1995 had nothing heroic about it. It was, in fact, death by the most shockingly un-African of causes – suicide.

Equally shocking was that five years earlier, in 1990, Tembo had been kicked out of the Bhundu Boys, a group he had helped attain world fame.

Yet less than a year before the fallout, Tembo had proved his legendary stage presence when he kept a predominantly white audience on its feet, deliriously singing along Shona songs. The show was held in June at a fully packed The Mean Fiddler, a popular venue for big musical shows then which is in Harlesden, London. Music critics dubbed the show “one of the group’s best live performances”.

The convivial Tembo would use his native Shona to greet the audience, urge them to ululate or clap at his shows and they would always oblige. He enjoyed it and the audience loved him.

Tembo is remembered for hits like Simbimbino, Hatisitose, Jekanyika and Chekudya Chese, among many others.

The genesis of his perfect harmonies and mastery in strumming the guitar could be traced back to his youthful days in the placid town of Chinhoyi about 115 km northwest of Harare.

It was a journey that started soon after Tembo completed his primary education and was employed by one Mr Gosllett as a gardener.

Tembo would ask the maid to pass him their employer’s guitar whenever their boss was away. He would play a few chords of Jimi Hendrix’s Hey Joe.

In the late 70s, Tembo teamed up with three other budding artistes, Franco Kaunda, Cephas Mashakada and Jacob Teguru and formed their musical group whose name is now obscure. Tembo and Kaunda were to later form their group, the Missing Tooth after Mashakada and Teguru had left to launch solo careers. They relocated to Murombedzi Growth Point in Zvimba and made it their base but later moved to Hurungwe where they began staging live shows.

Tembo always looked at ways of improving himself musically and academically. He tried many other avenues to achieve that like studying for Ordinary Level through correspondence, but his first love remained music.

His passion for music was to take him across the world, touring many countries, a rare achievement back then.

Tembo moved to Harare in 1979 and joined the Bhundu Boys in 1980.

Lead guitarist and singer, Rise Kagona, had assembled the jit outfit in the Capital City, Harare, in April 1980, the same month and year the country attained its independence. The reserved Kagona was also the leader of the band but the eloquent Tembo quickly asserted himself as the spokesperson and front man of the group largely because of his good command of English.

At the peak of his career, Tembo became so popular that at one point he, together with the Bhundu Boys, released a series of number one hits that shook Europe. Biggie Tembo’s song Hatisitose, stayed at the top of the music charts for 12 weeks and even outsold the late king of pop, Michael Jackson.

While still in England, Tembo won the Sony Award for a superb Radio 1 documentary that he co-presented with his best friend, Andy Kershaw, hosted a special for Channel 4 and appeared on the television programme, Blue Star.

But things began to fall apart in late 1989.

Conflicting narratives for the acrimonious divorce between Tembo and the Bhundu Boys were proffered but it appears jealousy destroyed the group.

Kagona accused Tembo of being bigheaded and a sellout who was secretly plotting to launch a solo music career with the help of the band’s manager, Muir, among other things.

Tembo hit back arguing that Kagona was jealousy of his popularity. He further alleged Kagona was pushing to have more of his songs featured on albums. Eventually Kagona kicked Tembo out of the group in 1990. Kagona, who is now based in Scotland, has often said in interviews Tembo quit the group on his own after insulting everyone and assaulting Gordon Muir, their former manager.

But then, “Dead men tell no tales”.

However, Steve Roskilly of Shed Studio, the man who first recorded the Bhundu Boys’ music said the story of Tembo, “was a disaster from start to finish”.

“He did not resign. He was fired. And he couldn’t take that. Tembo was the one who came up with the special songs. Tembo had the personality. The others couldn’t deal with the attention he was getting. It’s true that he was a volatile man. But the band made a terrible mistake when they fired him. Neither Tembo, or they, ever recovered.”

And Kershaw who regarded the late Tembo as the most naturally talented African to ever hold a microphone concurred. He described the decision to fire Tembo as catastrophic.

“The Bhundu Boys had great tunes, musicianship and a pop sensibility; they had the personality… In terms of personality, their big asset was Biggie. He was a great character on stage, a great communicator. The biggest mistake they ever made was to get rid of him. He was the front-man, the spokesman, the leader and the ambassador. Everyone loved him, and he loved that role,” said

Tembo pleaded to be readmitted into the band but Kagona refused.

He then tried to go solo with the help of the Ocean City band in Harare but the two albums he produced received a lukewarm reception from his fans.

Then depression hit Tembo resulting in him seeking solace in whisky, comedy and the church. It was almost at the same time that he learnt the man who raised him was not his biological father.

“All of that started after he was separated from the group,” his widow, Ratidzai told Robert Chalmers of the UK based Independent newspaper way back in 2005. “He suffered terrible stress. He began to drink whisky – lots of it, straight from the bottle. He said it would help him sleep, but it didn’t. He couldn’t sleep. He was up for days. He started to behave strangely. One day we were watching TV – this was towards the end, when we still had a place in England, a flat in Bristol. He kept saying he could smell burning; that something was on fire in the house. He was pacing around, looking for smoke, even though nothing was alight.”

Tembo was admitted in a psychiatric clinic first in Britain and later in Harare as he struggled to deal with depression.

He was later found hanging in the psychiatric unit of Harare Hospital.

“They told me that he broke free from his straitjacket and hanged himself in his room,” Ratidzai said.

Biggie Tembo was born Mhosva Rodwell Marasha in Chinhoyi. The town is famous for having seen the first skirmish between the Zimbabwean Liberation Army and Ian Smith’s Rhodesian Security Forces – a clash which launched the conflict that eventually led to independence. As a boy, Tembo was involved in the armed struggle as a messenger and lookout, and he liked to address friends, Kershaw included, as “Comrade”.

His legacy lives on in his music which is still as good to the ear today as it was more than thirty years ago in the 1980s.

Two of Tembo’s sons, Eriya and Biggie junior, are pursuing music as a profession and have recorded works. They say they want to take their father’s legacy to another level.

Perhaps it is true; heroes don’t die.